Exponent e

Sequences, approximations, and convergence

I wrote this on my laptop, so it may not display faultlessly on a mobile device. If possible, please use a desktop or laptop computer to view this post. If you must use a mobile device, you can either touch-scan left or right or use landscape mode.

I was intrigued by two problems presented in Ali’s Newsletter Beyond Euclid #167. He showed an approximation to e that uses all the 9 non-zero digits of our base 10 number system. I want to dig into that result today. I will do another post on the multiplication that yields a series of digits in order: 12345678987654321, and why.1

The Approximation

Let’s look at Richard Sabey’s remarkably good approximation to e that uses all 9 digits (except zero, of course).

Don’t worry about the minus sign. It’s just an instruction to take the reciprocal: put the term in the denominator without the minus sign. See N in the formula below.

This is a well known sequence that converges (gets close) to e as N gets large. Let’s take a look at some early values of the sequence:

Let’s evaluate some later values is the sequence and see what happens:

The approximation to e rounds off to an incorrect result, but it’s only out by a penny. Jacob Bernoulli made a calculation in the 17th century relating to "continuous" compound interest — he looked at what happens when you make the number of compounding periods per year arbitrarily large. In this way, he encountered the number e. See the calculation below.

At last! We have e estimated to five decimal places. But we had to go way out in the sequence to get there (it turns out that N = 200,000 only just gets us to five decimal places)2 so this sequence grows and converges to e very slowly. “Converges” means that you can find a number far enough out in the sequence so that all the numbers in the sequence after that are as close to e as we previously specified.

Since we don’t know what the numerical value of e is ahead of time, this sounds suspicious. Fortunately, there is a property of numbers we can use that states (roughly) that if successive members of the sequence get closer and closer together, it will converge to a limit, even though we may not know the numerical value of that limit. The property is called the Cauchy Property, named for a celebrated 19th century mathematician. (He is also known for a famous mistake — so there’s hope for all of us.)

So what’s the big deal with the number e? Well, that number turns up in many important places: as a base in logarithms, in approximations of large numbers, in statistics and physics, in a connection between the trigonometric functions and imaginary numbers, and at my kind of party. And that’s just for starters.

Let’s see if we can make up an argument that gives us the original sequence formula:

Our goofy friend in the Economics Department,3 who always seems to be broke but comes up with money when he needs it, offers us a deal. He’ll give us 100% interest per year. But he also offers us a number of different compounding periods per year. We can invest one dollar and get another dollar at the end of the year. Or, we can invest one dollar and get 50 cents half way through the year. If we let the investment ride for the remaining half of the year, we get another 50% of the $1.50 we have at the half way point: $1.50 + $0.75 = $2.25. We can choose quarterly compounding (4 times per year), 12 times per year, and so on. Sweet! The formulas look like this:

As you can see, the extra compounding periods increase the investment, but we’re also dividing the original interest rate by 2 or 4. That seems to cut down on the 100% we thought we were getting. The investment is cooling down, but is there a limit to its growth? Let’s look at what happens with even more compounding periods in the year:

With daily compounding, we’re starting to close in on the value of e. Of course, banks don’t offer a 100% rate. In fact, their continuously compounded rate is usually less than the standard rate because the many compounding periods add to the year-end balance. Our main concern here is that this example leads to the formula. What Richard Sabey did was to choose a very large numerical value for N so that he would get a very accurate approximation. It turns out that the exponential he used inside the brackets is equal to the exponential outside. He cleverly used the rules of exponentials so that he includes all the digits from 1 to 9.

Conclusion

We’ve seen a formula for estimating e, and we found that it’s the same as the continuous compounding formula. We worked out a motivating example for the sequence. Finally, we resolved the exponentials and showed that they were equal. We did not prove that the sequence converged to the result; this is a technical question we left to an example in a footnote. Also, we did not explore e as the base of logarithms. I will leave you with a taste of the connection between e and imaginary numbers (also called complex numbers):

Euler published his formula in 1748 in his two volume book Introductio in Analysin Infinitorum that lays the foundations for analysis (the theoretical side of Calculus). Other mathematicians before Euler knew of the result, but they didn’t understand or express the connection to imaginary numbers properly or coherently. Euler manipulated the known series for the sine and cosine functions to get the result. He was lucky that when the full justification came about 100 years later, he was correct.

This footnote is to learn or review some terminology and notation about sets and functions. Visit here at any time to get some grounding.

Sets

A set is a collection of objects, which will often be numbers. A member object of a set is called an element of the set. Each element occurs only once; otherwise, it is not a “set,” it is a multiset, but we won’t need that concept. We symbolize a set with a capital letter. The names of the objects in the set will be enclosed in curly braces: { and }. For example, S = { one, apple, Kevin, 67, 30 }. We often speak loosely and use an ellipsis to mean “follow the pattern, it’s obvious,” like this: T = { 0, 5, 10, 15, … }. The order of the elements doesn’t matter. Later, we’ll learn a more precise way of specifying exactly what we mean; that’s called a notation, and some are better than others, which can often be a matter of preference or opinion. (I find Bourbaki’s notation annoying, and if he existed I’d tell him that.) Anyway, back to sets.

Set Operations and the Empty Set

The union of two sets A and B is the set consisting of each of the elements (if any) of A and B, without duplication. The intersection of two sets A and B is the set consisting of elements which are in both A and B (if A and B have no elements in common the intersection is the empty set). We must address what the “empty set” is and why we need it. It is symbolized by ∅ and is such that, for any set A, A ⋃ ∅ = A and A ⋂ ∅ = ∅. That reads respectively “The union of A and the empty set equals A” and “A intersect the empty set equals the empty set.” We say that the empty set has nothing in it. A subset A of S consists only of elements of S, but not necessarily all of them. A subset A of a set S is written A ⊂ S (where A does not equal S) or A ⊆ S (where A may equal S). The empty set ∅ is considered a subset of every set. Thus the set itself and the empty set are always two subsets of any set; subsets other than these two, if any, are called Proper Subsets.

Functions

A function is a set. The elements of the set are pairs of objects (often number pairs). There are several rules that govern whether a set of number pairs is considered a function. I will begin with a broader concept. Suppose A and B are sets; we will suppose that neither set is the empty set. The Cartesian Product of A and B is written A ⨉ B = { (a, b) such that a ∈ A and b ∈ B } . The “∈” symbol is read “is an element of.” A subset of A ⨉ B is called a relation. A function is also a relation, but there are some extra rules and terminology about functions.

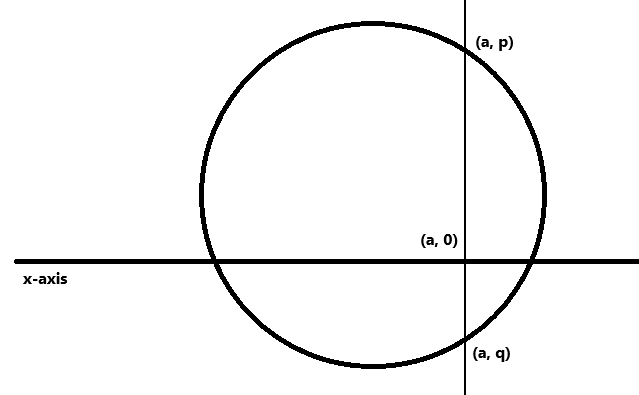

In the case of a function, the set A is called the domain; the set B is called the co-domain. Each of the elements of A must occur as the first entry in some pair. Furthermore, each element of A must be paired with at most one element of B. A function is also a subset of A ⨉ B (and therefore a relation). The reverse is not true: the circumference of a circle is a relation but not a function. To see this, pick a point on the x-axis (or domain) within the circle; there are two distinct points on the circumference both above and below the point on the x-axis. This violates one of the rules for being a function:

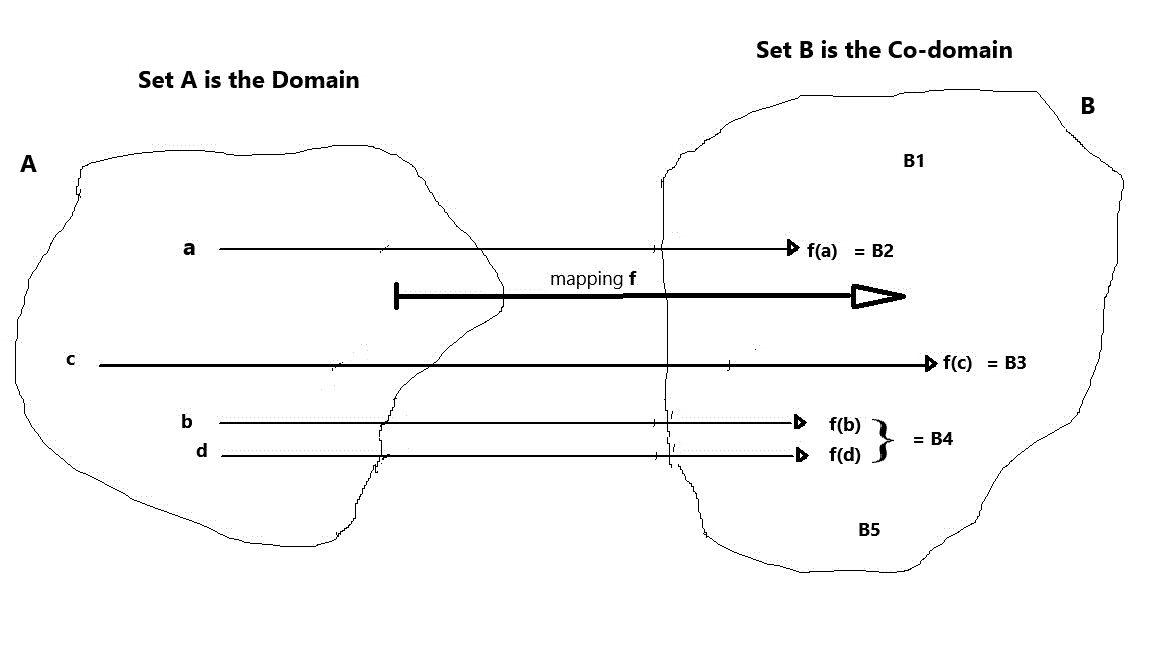

The words “mapping", “operator,” and “sequence” are all synonyms for “function.” The different words are used mostly to draw attention to the fact that the sets A and B contain special objects or features. I like the word “mapping,” and the best way to illustrate a function is with a picture. First, let’s specify an example function using the “dull as dishwater” method: the domain = A = { a, b, c, d}, the co-domain = B = { B1, B2, B3, B4, B5 }, the function f = { (a, B2,), (b, B4), (c, B3), (d, B4) }. This is often specified as follows: f(a) = B2, f(b) = B4, f( c ) = B3, f(d) = B4. Notice that every element in the domain was used, but not every element in the co-domain had something mapped to it. Also, some elements of the domain mapped to the same element of the co-domain. Here’s the picture:

A function is called an injection when it maps each element of the domain to a different element of the co-domain [ f(x) = f(y) implies x = y for every x, y ∈ A (the domain) ]. Our example function f is not an injection: [ B4 = f(b) = f(d) but b and d are different elements of the domain ]. A function is called a surjection when it maps so that each of the co-domain elements has something from the domain mapped to it. Our function is not a surjection: our function does not map anything to B1 ∈ B (I only need one counterexample, even though there are 2). In the example function f, I cannot simply call B the domain and A the co-domain by reversing the arrows in the picture. Can you see why not?

A function that is both an injection and a surjection is called a bijection. If you start with a bijective function f with A as the domain and B as the co-domain, you can “reverse the arrows:” you now have a (new) function from B to A. Given its history, the new function is called the inverse of f and is written f⁻¹ (that’s f with a superscript of minus 1, not to be confused with the numerical reciprocal). The subset of B (the co-domain) of all elements that have something from A (the domain) mapped to it is called the image under f (or the range of f). (The image under f will be the whole of B if f is a surjection.) In our example function f, the image under f is = { B2, B3, B4 } ⊂ B (which is a proper subset of the co-domain B because f is not a surjection).

Sometimes there is an algebraic structure on the sets. Mathematicians are interested if they can say anything about whether the mappings “preserve” structure (on Groups, Fields, or topologies) from one set to another. For example, are there analogues to our usual calculus operations on a function?

Here are the other names we use for “function",” and why we distinguish between functions:

Function: We typically use this term when the domain A and the co-domain are sets of numbers. For example, A could be a set of people, and B a set of possible ages (usually B = ℤ). Or, B is a set of possible heights (usually B = Q or B = ℝ, the set of real numbers). In the first case, the function is called “integer-valued";” in the second case, the function is called real-valued (Rational-valued sounds a bit odd). If B were a set of complex numbers, the function would be called “complex-valued.”

Sequence: You’ll here this term when A = ℤ⁺ (the set of positive numbers). Instead of writing the usual f(n) or X(n) or Y(n), we’ll write xₙ or yₙ. Sometimes, for convenience, we’ll start a sequence at 0 instead of 1. The set B is usually the Rational numbers ℚ or the Real numbers ℝ.

Operator This usually means there is an operation (like addition or multiplication) within each set, though the operations do not have to be the same in different sets. Inquiring algebraists want to know what restrictions must be placed on the mapping between A and B so as to “preserve” the algebraic structure from the domain into the co-domain. They describe the special mappings as operators, or specifically as homomorphisms or isomorphisms. The objects in A or B are not necesarily numbers: they could be matrices, vectors, permutations or something more exotic.

Mapping This is the term that is used for a generic function where the sets do not fall into any previous category.

This turns out to be a surprisingly messy problem:

“Converge to a limit” means that the sequence gets close to a particular number, called the limit. It is specified ahead of time how close you need to be: for example, you could be given ε = 0.001 (we stipulate that ε must be a positive number). Then you have to find how far out in the sequence you have to go so that all successive values of the sequence are within ε of the limit (the final numerical result).

You’d like to find a formula in terms of ε that will tell the reader how far out he or she needs to go given whatever value he or she chose for ε. Therefore, you want N (the sequence identifier) in terms of ε; this is sometimes written N(ε) to indicate N depends on ε. That’s called “function notation.”

Here is a simple example of finding the limit:

Notice that there’s a disconnect between the actual value of the limit and proving that a value actually is the limit. How you come up with the numerical value of the limit is a creative process that’s up to you. Usually you guess or make some algebraic manipulations (a purely formal process of working with symbols). After you have this value, you prove that it is really the limit by using the method above. If you simply don’t know the numerical value of the limit, you can still prove it exists (the sequence, or series converges). Usually, you prove the sequence or series converges by comparing it to series that is known to converge (the Comparison Test Theorem):